When you manage to extend the life of your goods both successfully and qualitatively, you are buying time in the economic value circle. Things tend to last longer with fewer resources and with less money. Is that as simple as it sounds?

What does the pocket knife you inherited from your dad have in common with that pair of leather boots on which you once spent all of your savings? The answer is that you treat them like your favourite stuffed toy from when you were four years old! Sometimes you treat them roughly, and sometimes with affection. Sometimes you ignore them, while other times you give them lots of attention. You check to see if they are in good shape, or if a line or scratch has added to the story they tell. You love those items, and so they stay with you, year after year.

It is the basis of the economic model called ‘life extension’. It is not an end in itself; it is the process of extending the functional life-cycle of a product through proper maintenance and repair, over and over again. By giving it a second life with someone else in the next phase, or by (partially) giving it another purpose.

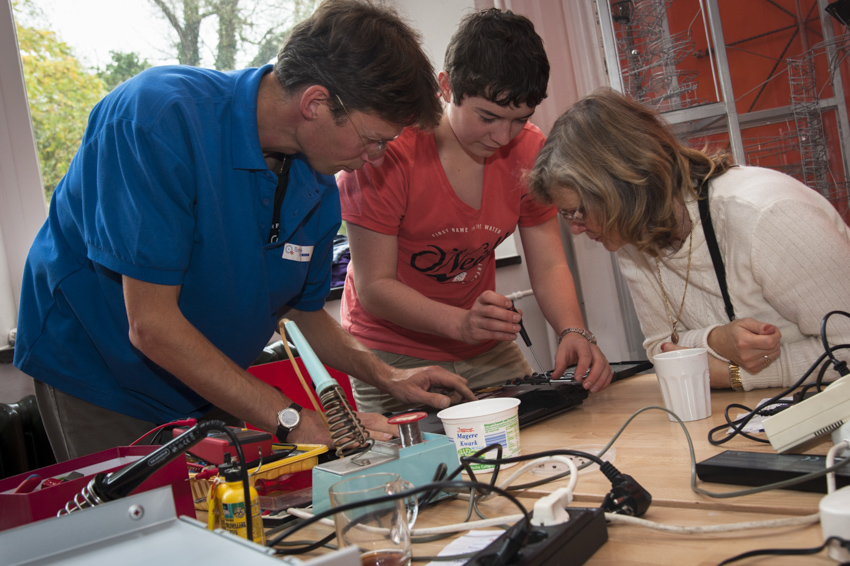

Photocredit: Martin Waalboer/Repair Café International.

What was the norm roughly a hundred years previously made a nice comeback a few years ago with Repair Cafés. They restore the reflex to fix something when it’s broken which is indeed a good thing. The idea originated in the Netherlands where, in 2007, Martine Postma wanted to commit to sustainability at the local level. In Flanders, the Flemish Region of Belgium, Netwerk Bewust Verbruiken (Conscious Consumption Network) was soon on board.

Successful recovery cafés popped up all over the country, and everyone joined in. The recipe for success has more than one ingredient, e.g. there are tools which you might not have at home, there are volunteers who are knowledgeable, and most of all, there is a good atmosphere with coffee, cookies and other people. Of course, the items benefit from all of this.

People are becoming familiar again with the insides of things, and with screws and wires. In this way, you literally forge a bond between yourself and your belongings. After all, it’s more about the attention you give to your stuff, rather than just about the repair itself. The more effort you put into something, the more you might be inclined to take good care of it, which is crucial to its longevity.

Let’s face it: things are all too often simply replaced rather than being repaired. The cost of the repair plays a major role; imagine that your appliance is manufactured in a low-wage country, and the repair is done by a local technician. You immediately know where the shoe pinches. The government could play a role in this by applying a lower VAT rate to repairs than they do for new purchases. However, we’re still waiting for this kind of meaningful policy change.

Cost is not the only challenge. Of course, you don’t intend to wear rags just to save you having to buy new clothes, and you don’t want to deal with that rickety appliance all the time. Extending life goes a lot further than the consumer’s reflex to repair things or to have them repaired. Thus, we should also focus on the producer. After all, repairability starts in the design phase where the choice is explicitly made to use quality raw materials and to design repairable products. A device may be made in such a way that it is not repairable because you cannot disassemble it. Can you open your mobile phone to replace the battery or another part? We don’t question it because we may get bored with our phone even before it breaks, and phones are increasingly becoming closed, glued boxes. It’s all or nothing nowadays. The Dutch brand, Fairphone, offers a radically different vision: the phone they’re marketing consists of a detachable unit whose parts you can actually replace by yourself! An extra advantage of this modularity is that, if you want, you can equip your phone with a better camera and/or more memory.

Even if you can still open your product with a screwdriver, that’s no guarantee of repairability. We all know the shocking news stories where programmed obsolescence in electrical appliances came to light. This is an extremely cynical and damaging attitude towards Mother Earth, and it is a major headache when it comes to government regulation. A less obvious example is when a manufacturer does not manufacture spare parts. The brand SEB, which is a producer of small household appliances, feels that this should change. They set an example by committing to deliver products that are repairable all across Europe for up to ten years after purchase. As a consumer, the minimum you can do is to focus on the kind of production approach where after-sales service is an essential part of the cost. After all, isn’t longevity an interest that we as consumers share with our planet?

No matter how hard we try to make the repair reflex to become an automatic response in each of us, extending lifespan at all costs is not always appropriate. For example, your appliance may be an energy glutton and therefore the environmental benefit of repairing it may be negligible or even negative. In that case, it would be better to get a more energy efficient version.

Photocredit: Martin Waalboer/Repair Café International.

If you’ve had enough of a product, even though it is still in good shape, a second life can be considered. The second-hand market has been a booming business in recent years. Coronavirus aside, flea markets are the mainstream place where countless told stories take a plot twist. It all starts with the adrenaline of finding that special dinnerware, that vintage wooden table and the items for your teenager who is going to college.

It is precisely this feeling that De Kringwinkel (thrift store) has elevated to its business model. It got rid of the dusty image of a thrift store and made resale hip. The business model doesn’t stop there though, because thrift store repair services restore pride to wonky wardrobes and washing machines that were deemed to be lost.

At the same time, they train a diverse range of people in the creative knowledge needed to give things a new breath of life. For those who attach meaning to their belongings and yet have a good reason to get rid of them, granting them a second youth is a nice way of saying goodbye.

When goods are made with quality parts, are well-maintained and can be disassembled, they hold another advantage. They can form the basis for a new product when the time comes. When parts of a product or device are reused to make a new product, we call it refurbishment or remanufacturing, depending on the change needed. In other words, one uses little energy or new raw materials to achieve a valuable and new result. In the case of refurbishment, major maintenance or a new battery may suffice, as Green Mobile does for smartphones. In remanufacturing, devices are disassembled, and parts are reused.

Pami Workspace Designers is a company that has been designing and creating office concepts for decades. During that time, their focus has evolved from minimal cost to minimal life-cycle cost. Sustainability, longevity and the goal of working waste-free became focus points for them. What do you do, for instance, when you see that increasingly less paper is being used and the typical robust roller door office cabinets are just standing there idly? Some out-of-the-box thinking is useful here. The company did just that by linking this surplus to the need for central lockers for all those flex workers who had joined in recent years and didn’t have a fixed desk. The lockers can even stay where they are, as the company will come and do the transformation on the spot.

Meanwhile, hobbyists enjoy designing all kinds of upcycled conveniences at home. Flat bicycle tires become indestructible belts, an old bottle without a bottom becomes a hanging vase, an awkward wobbly chair becomes a wall-mounted coat rack, the old bathtub becomes a herb garden outside, and discarded T-shirts combine to become a colourful rug. Professional creators also like to inform others that they work with materials that are wear-resistant, or better still, that age beautifully together with the user.

Interior designer, Hanne Beutels, has launched her own handbag label with great verve, and with recycled and vegetable-based tanned leather. Her manufacturing method assures you that you have the item for life. The Belgian e-bike start-up Cowboy also thinks ahead. Within their Cowboy Circular programme, they offer bikes that have been minimally used in, for example, test ride programs or showrooms, and bikes which have been returned by customers. At a steep discount and fully embellished, they are waiting for a loving owner.

Interior designer, Hanne Beutels, has launched her own handbag label with great verve, and with recycled and vegetable-based tanned leather. Her manufacturing method assures you that you have the item for life. The Belgian e-bike start-up Cowboy also thinks ahead. Within their Cowboy Circular programme, they offer bikes that have been minimally used in, for example, test ride programs or showrooms, and bikes which have been returned by customers. At a steep discount and fully embellished, they are waiting for a loving owner.

It is a special landscape where raw materials and energy are under great pressure and where, at the same time, the discarding of goods is assuming staggering proportions, where even brand-new products are sometimes no longer considered to be saleable because they have already made a return trip in the post. As a creative maker, you can experience golden times, where only your own imagination determines the limits of what is possible. You can already factor in the second and third lives of a product in the design phase, opt for a modular design, see the mountain of items as a resource mine. You can inspire the users of your creations to keep living their story with the objects they gather around themselves.

—

Are you already a sustainable entrepreneur or do you want to get started? Download the free Leap Model, which is a step-by-step plan to get your organisation on track sustainably.

This article was created with the support of Circular Flanders.

string(3) "yes"Mollit duis Lorem amet veniam minim ad.Voluptate commodo labore aliqua quis esse aliqua.Veniam tempor elit velit non.